Imagine you are navigating a large raft in the middle of the sea, and, all at once, every single one of your passengers falls out. The waters are extremely rough and so the emergency is high.

What do you do?

You, of course, reach for the life preservers only to discover there aren’t as many as there are people. You, nevertheless, throw out what you have at your disposal in the hope of saving passengers quickly, so that you may reuse the life preservers and give everyone a fighting chance. You notice, however, the tethered ropes are frayed, making their durability uncertain. You then detect a slow leak in your raft. Your flares have also gone unanswered, as the skies are dark and cloudy. And your navigation device has charted an unknown path.

What do you do?

As you might already sense, I’ve embellished the metaphor somewhat in order to make comparisons to the various options we often find amidst our organizational practice.

What do you do?

The question really becomes, what do you attempt first? Do you tend to the leak—shoring up organizational operations so that your vessel may stay afloat upon and capable of maneuvering an unstable cultural landscape? Do you address your navigation system—clarifying the organization’s intended goals and creating pathways of promise for your community members, knowing that the destination may not be as welcoming? Do you continue to send out signals—messaging out into the world your intentions and desire for partnership toward institutional change, even if those words are ignored? Or do you acquire the resources to obtain more life preservers—continuously challenging philanthropy to directly support those most impacted, even if that compassion is limited or misdirected toward the symptoms of the crisis rather than the root cause of there not existing enough boats to begin with?

In the early years of Assembly, Allison and I penned a yet to be published essay, entitled Imagination as Privilege, regarding what we witnessed as “failures,” as they emerged in even our most ambitious and courageous participants. If multiple and overlapping systemic failures manifest themselves as ongoing, individual derailments or self-imposed landmines (as I’ve called the personal breakdowns), then:

The astute and unspoken question must be: who are you (anyone) to even propose that I imagine myself or my life outside of my current situation?

Certainly, factors such as poverty, lack of resources, access to education and health care foreclose possibilities. That story is not new. It’s less common to consider the ways in which these factors limit subjectivity, and thus the willingness and capacity to imagine. Futurity, a language artists speak fluently, is not always accessible.

And yet, we believe there is a power in artistry:

But artists live by engaging a process of creative review. They are constantly inventing images and languages to reframe their surroundings—to offer new meanings. If artists move through the world by stretching their own subjectivity and projecting it onto imagined possibilities, they are also uniquely suited to impart this strength where it has been systematically removed.

When and where can these imagined possibilities then emerge? Even if imagination is a gift for all, it is not a given for some. So to inspire, we need to work extremely hard. We must also recognize the reality (and requirement) to fail over and over again, alongside our community members. And yes, this can feel like an exercise in defeat.

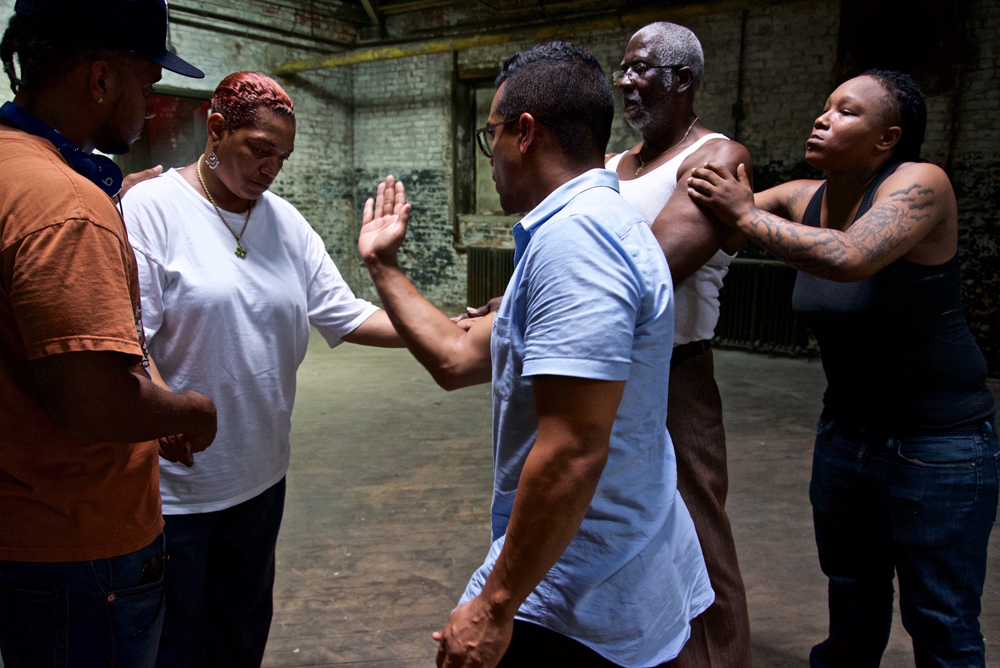

While I don’t have a single answer for the metaphorical question of our precarious lifeboat, I do know that we’ve committed to firing the flares, charting our course, and securing additional life savers. I also know that there is one option that often goes overlooked: strengthening the frayed lines. Over the last few weeks I have witnessed each and every staff member interact in the space—creating emotional bonds with our artists, young people, board members and practitioners… and with one another. This intangible connection is the very thing that imbues art with possibilities not offered out in the world—imagining a community built on resilience and safety, even as realities force failure into individuals’ lives. When witnessed, it becomes clear that it is the strength of the lines that make all the other options of emergency response possible… and worthwhile.

Much love to you all.

Shaun