In truth, I felt extremely overwhelmed by the caliber of artistry in my midst and subdued my usual outgoing spirit for an insular yet productive mode of introspection. By late morning of my first visit with David, I had already exercised on the pull up bar installed outside my studio, worked for hours in the wood shop and consumed three cups of coffee without speaking a word to anyone. I was nowhere to be found when David entered my studio. After finally waking up from my mental state, I rushed back to my studio so I might greet my visitor professionally and instead nearly dropped an 8 x 4 foot sheet of plywood on his head.

David brushed off the slight injury, near tragedy, quietly looked around the filled studio and said something to the effect “I understand why self-portraiture is important to you and your practice. It makes sense for a man your age to look at himself…”

Interestingly, David did not then nor has he ever provided a direct critique of my work. Instead, he has treated me like a son. And as father figures (who are not your actual father) often do, he continues to provide an example—a way forward with dignity and grace and what seems like an air of confidence impossible to achieve.

I try to be that for all the young men I work with and for.

Upon the invitation to write this essay, I thought that I would interview David, asking him for his insight on the potency and efficacy of self-portraiture. I’ve come to understand that the answer is already provided within any question that I might ask him and that he has already told me all there is to know… “it makes sense.” To look into the eyes of David (in, for example, his 1953 or 1956 Self-Portraits) is to examine the way he as a young man viewed himself with both inquiry and curiosity. There is a calm confidence locked in those eyes that then lead you to his signature mustache and closed lips. There is no tightness in his mouth, however, just a delicate closure belying what one feels must be a wealth of information ready to be shared. This young man wants to be acknowledged and seen. But by the time we arrive at Self-Portrait as Beni (“I Dream Again of Benin”), July 13, 1974, we have a set of eyes that dare the viewer to return a gaze. Eighteen years after the earlier self-portraits, we now have a man whose wisdom appears to be withheld, offered only if and when we, as witnesses, are deemed ready.

I might say that to peer into his self-investigation is an invitation to do so for yourself. In this way, I stare into his painted eyes in order to stare into my own. For a young black man to look at his own face with pause and care is to also question, with discomfort, what it is that people hate about you. At some early stage, a young black man must raise up a mirror to the world not only to define who and what he may be, but also who and what he is not. In this reflexive manner, we construct an appearance of ourselves, which acknowledges others’ misperceptions—of our bravado, our speech, our mannerisms… our blackness. We develop a system for constructing a selfhood while contending with this mirror—one which displays back others’ own projections of desire, ambition, failure, and fear.

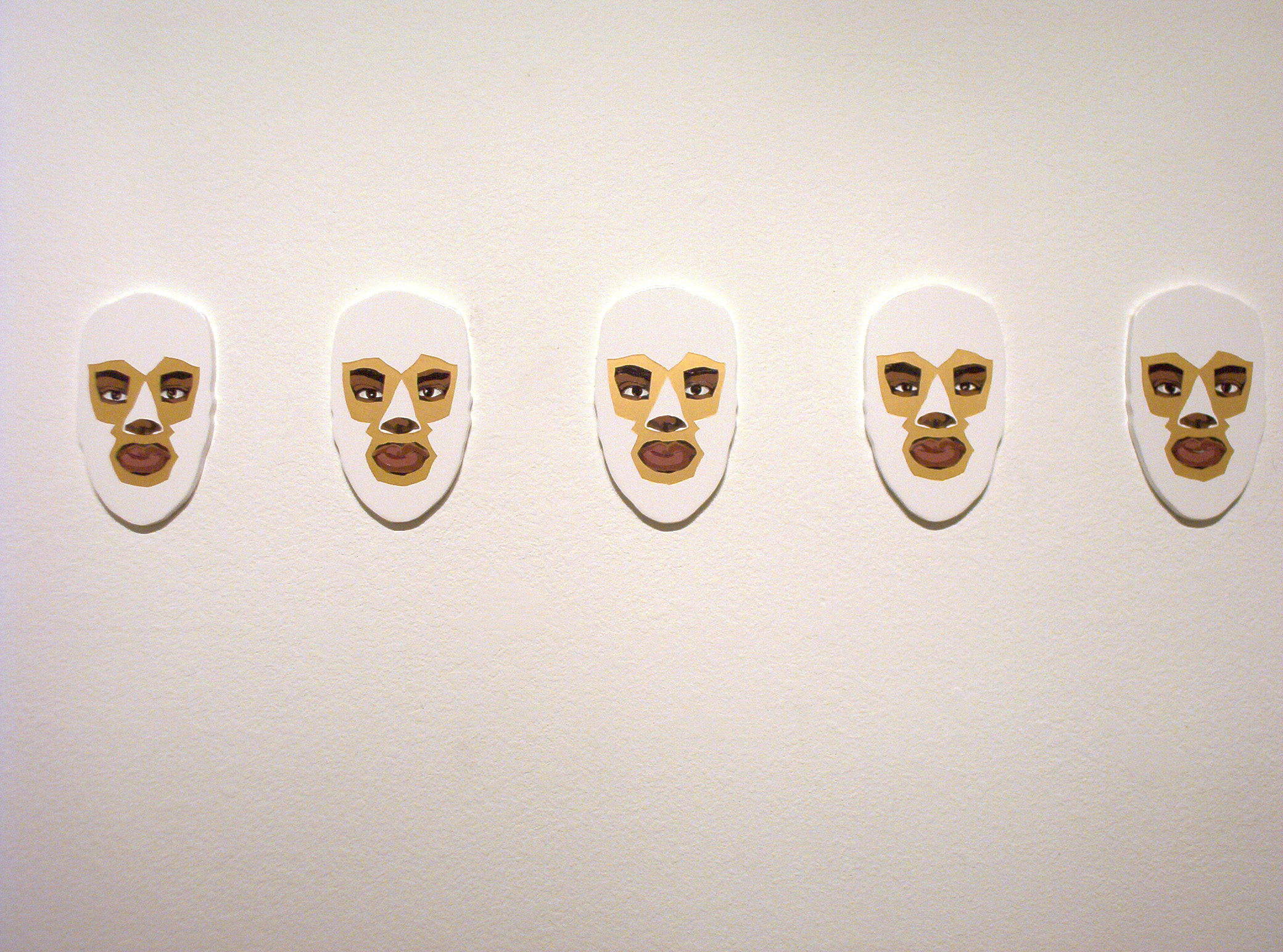

A self-portrait, then, is no easy task. It will always stare back at us asking if we are telling the truth. That day David first entered my studio, he saw not one but thirty-two self-portraits – each with a slightly different stare, all of them direct but each with its own level of searching. Each luchador mask reveals only as much as the portrait’s eyes would allow its subject to convey, maybe with a slight variation of an eyebrow lift or parted lips. The masks withhold most information regarding my facial structure and expression and disguise much of my brown skin… and yet say so much. Each day I spent in that studio those thirty-two faces would ask something else to and of me—to speak truth into my construction of manhood and blackness and to, moving forward, leave nothing withheld.

As I believe David did and continues to do when seeing me, there is a resonance that occurs when I connect with another young brown or black man. I am attune to their searching as David was of mine.

And rather than offer suggestions or advice, I tend to forward a question that may move them along their own self-inquiry—one which is an attempt to balance self-perception and that of an outside world’s that would rather he (we) not exist. In my work in court diversion, the young men that share space with me have been obligated to be present, mandated by a justice system sometimes for crimes as defined by that same system, other times for crimes that in any other community of non-color would be deemed only a mistake. In the details of their narratives, as shared by them during a visual storytelling workshop process, I hear language that is quite often not their own, but is instead a framework of criminality that has been imposed on their bodies by the media and all the spheres of society that devalue their lives on a consistent basis, including their schools, homes, and the streets. We do the work of looking more carefully into their stories to find meaning that is more their own; never forgetting the version of us floating around the world, defined by someone else yet dictating our movements and constraining our options. And yet, we find value in ourselves when creating a quiet self-perception that we can always return to for confidence, awareness, and comfort; for all those times in which someone else would rather we not be. We look back at our own faces because we are more, we are love, and simply because it makes sense.